This question is at the center of a heated debate. To answer it, it is essential to shift the focus from judging which is “better” or “worse” to analyzing the facts.

In general, the differences between the various types of eggs on the market are not so much in their basic nutritional composition, which is very similar for all chicken eggs, but rather in their flavor, texture, and the implications of the production system.

Let’s look at the differences between eggs from intensive farms and those from hens of other breeds and farming methods.

Eggs from intensive farming

These eggs come from hybrid breeds of hens that have been genetically selected to maximize egg production (over 300 eggs per year) and are raised in high-density sheds (barn-raised). All farms are gradually transitioning from the old cage system to different cage-free systems.

Breeds used – Industrial hybrids (e.g., Hy-Line, Lohmann) are not true breeds, but strains optimized for productivity.

Taste and quality – The flavor is very standardized because the hen has a strictly controlled diet and does not have the opportunity to supplement its diet with grass or insects. The yolk tends to have a uniform “yellow” or white color depending on the selection to which it belongs.

Texture – The texture is consistent and standardized, as are the size and shape of the egg.

Availability and price – These are the most common and affordable eggs on the market, with the lowest consumer price.

Eggs from various existing breeds of hens (free-range, outdoor, organic)

These eggs come from purebred hens (such as Marans, Araucana, or the Dual Purpose breeds we have already mentioned here https://moreaboutchicken.com/is-there-a-chicken-that-can-provide-both-meat-and-eggs/ ) raised in systems that offer more space, such as free-range, outdoor, or organic farming.

Breeds used – Pure breeds such as Wyandotte, Marans, Araucana, Leghorn, and many others are used.

Taste and quality – The flavor can vary greatly depending on the breed and, above all, the diet. Hens that are allowed to roam freely supplement their diet with grass, insects, and seeds, which can give the yolk a more intense color and the flavor a greater complexity.

Texture and appearance – The shape, size, and color of the shell vary greatly depending on the breed. For example, Marans eggs have a chocolate-colored shell, while Araucana eggs are blue.

Availability and price – They are less available in large supermarkets and are more easily found in specialty stores, directly from producers, or at farmers’ markets. The price is generally higher, reflecting higher production costs and lower volumes.

Native breeds – There are thousands of small farmers who raise native breeds whose eggs can vary greatly in size, color, nutritional characteristics, and flavor. But what are native chicken breeds? Native breeds are those that originated and developed in a specific geographical area. Unlike commercial breeds, which are selected for maximum productivity, native breeds have adapted over centuries to the climate, environment, and farming traditions of a particular region.

Their main characteristics are:

Hardiness and resistance – They are more resistant to disease and better adapted to the local climate.

Foraging ability – They are often excellent foragers, able to find part of their food on their own.

Less productive – They lay fewer eggs and grow more slowly than commercial hybrids and offer niche products, with characteristics that vary depending on their genetics, the area in which they are raised, and the care provided by individual farmers.

Genetic value – They represent a fundamental heritage of biodiversity, valuable for conservation and research, even by large groups that genetically select animals for “industrial” reproduction.

In Italy, examples of native breeds include the Livornese, Padovana, Valdarno, and Cornuta di Caltanissetta.

How widespread are small farms?

After a sharp decline due to the advent of intensive/protected farming, small farms are experiencing a renaissance. Although their numbers are still small compared to large industrial farms, their popularity is growing due to several factors:

Consumer demand – There is a growing demand for high-quality, short-chain products with a recognizable history and ethics.

Biodiversity conservation – Many small farmers are passionately dedicated to preserving native breeds that would otherwise be at risk of extinction.

Passion for traditional farming – Many people, even in urban or peri-urban contexts, choose to raise a few chickens for self-production, rediscovering a connection with nature and a more ethical form of farming.

It must be said that small farms are obviously not for the mass market, but they are growing in number and play a useful role in protecting biodiversity and responding to a type of consumer who demands certain characteristics, often only for aesthetic reasons.

The main difference between the various types of eggs is not in fact in their basic nutritional composition, but in the way they are produced and what this results in, both in terms of flavor and variety.

The key point is that the genetic diversity of native breeds can lead to differences in certain qualities of the final product, in this case the egg, which is different from defining them as ‘quality’ in the strict sense. Commercial breeds have been selected to maximize production (egg quantity), while native breeds, often more rustic and less prolific, may have genetic characteristics that influence other parameters, such as nutritional composition.

Genetics vs. nutrition: differences in lipid profile are likely to be a combination of two factors. Of course, breed genetics play a role, but the way these breeds are raised (often with greater freedom of movement and a more varied diet, including grass and insects) significantly affects the nutritional qualities of the egg. The diet of a conventional chicken, on the other hand, is standardized and controlled.

The value of biodiversity: Native breeds, although less productive in terms of numbers, are often more resilient and better adapted to their environment. Their value, including in nutritional terms, is often used to support their conservation.

Implications for consumption: the perception that not all eggs are the same needs to be explained: although conventional eggs offer a solid basic nutritional value and are more accessible, eggs from native breeds or more sustainable farming systems can offer “added value” in terms of flavor and composition.

Scientific research indicates that differences exist, but the “suggestive” element is the positive interpretation of this data, which prompts reflection on the importance of safeguarding biodiversity and promoting local and sustainable production systems.

The focus of the debate often and easily shifts to food quality. To offer an objective and neutral view, it is therefore essential to avoid defining one egg as “better” than another in absolute terms and instead provide the tools to evaluate the differences.

The answer is that no egg can be said to be universally “better” than another. However, it can be said that they are different and that the choice of the “best” depends entirely on the consumer’s priorities.

But how can we evaluate eggs objectively, taking into account the various factors that influence them?

Instead of judging, we can compare eggs on multiple levels, providing people with the tools to distinguish between objective data and real differences on a case-by-case basis.

Nutritional profile

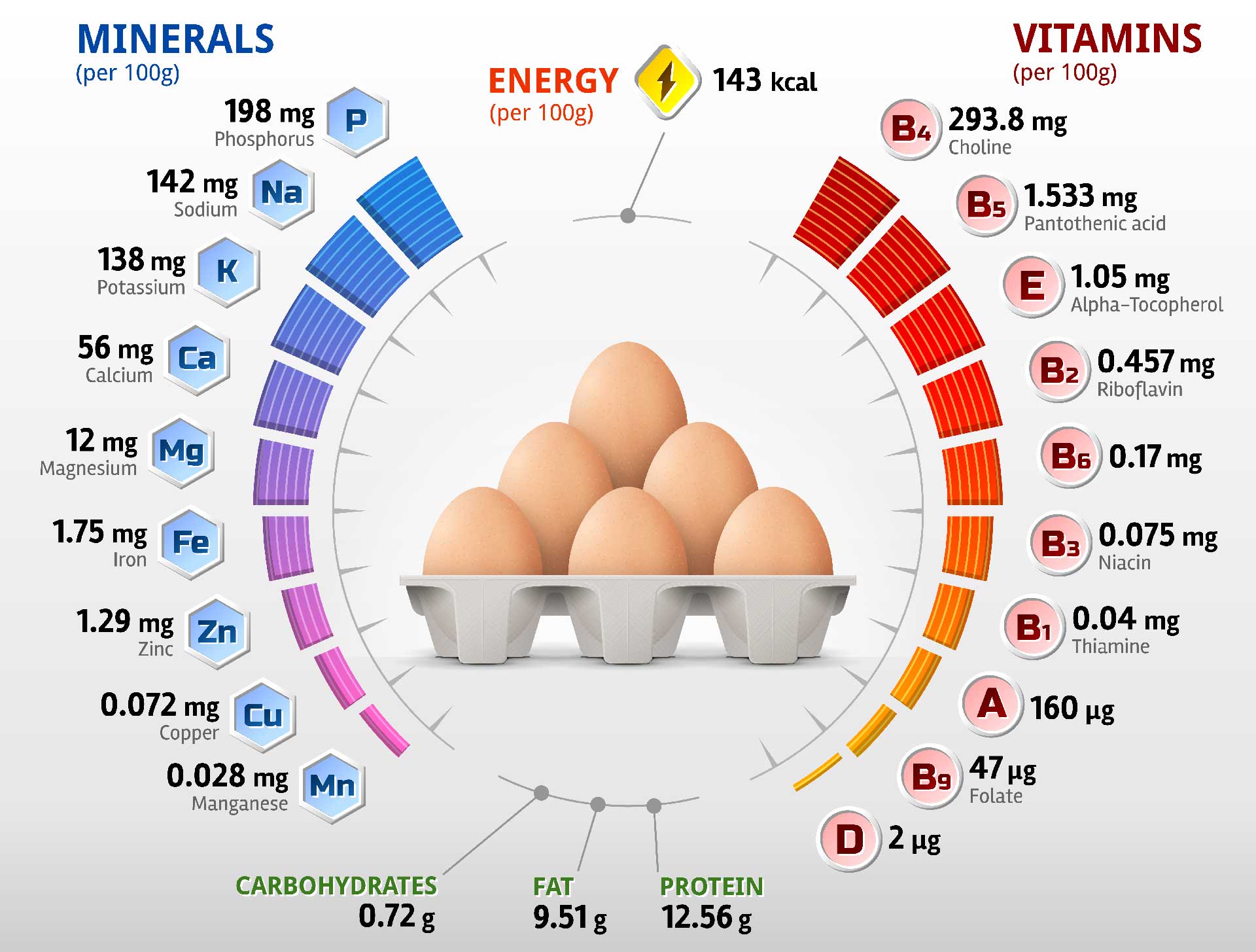

The objective data: the basic nutritional composition (proteins, fats, main vitamins) is very similar in all chicken eggs.

The differences: significant variations concern micronutrients. Hens that are able to roam outdoors, enriching their diet with grass, insects, and seeds, tend to produce eggs with a richer profile of Omega-3 fatty acids and certain vitamins (e.g., vitamin E) than hens that consume a controlled and standardized feed.

Sensory quality

The objective data: the taste, color, and texture of eggs can vary considerably.

The differences: eggs from free-range or outdoor hens, especially if they are a non-industrial breed, tend to have a darker yolk and a more intense and complex flavor. This is the result of the variety of their diet and the characteristics of the breed. However, the preference for a more or less pronounced flavor is subjective.

Animal welfare

The objective fact: the living conditions of the hen are the factor that most affects the difference between eggs.

The differences: intensive farming aims to maximize production efficiency by keeping animals in environments that may appear to limit their space (which, as we have seen in other articles, is relative due to the fact that these animals love to be in contact with their fellow creatures). Organic or free-range farming guarantees more freedom of movement and allows hens to express their natural behaviors more easily, which is a fundamental criterion for those who prioritize certain characteristics of farming.

Cost and sustainability

The objective fact: different forms of farming have different impacts on the economy and the environment.

The differences: eggs from intensive/protected farming are produced efficiently on a large scale and have a lower cost. Purebred or organic farms have higher production costs (for space, feed, yield, and care) and, as a result, a higher consumer price. Their environmental footprint can be more or less sustainable depending on the agricultural practices adopted.

Therefore

It is not scientifically correct to claim that one egg is universally better than another. Each egg is the result of a different production system, each with its own pros and cons.

However, an objective view leads us to say that the choice is not between a “good” and a “bad” system, but between two systems that manage welfare and the environment with different priorities and models. The choice therefore depends on the definition of welfare and sustainability that the consumer considers most important.

Quality is not a single concept, but the sum of factors that each of us, based on our own values and needs, chooses to prioritize.

Attention to animal welfare and the environment is not exclusive to non-intensive farming.

Animal welfare: definition and different approaches

Intensive farms care for animal welfare, especially with regard to health. Their focus is on disease prevention (through vaccines, disinfectants, etc.) and timely treatment to ensure that the animal does not suffer and that production does not suffer losses. The goal is a healthy and productive animal.

However, the notion of welfare in non-intensive (organic, free-range) farms is based on a different philosophy. Here, welfare is not just the absence of disease, but includes the possibility for the animal to express natural behaviors, such as:

Scratching and pecking in grassy soil.

Taking dust baths to clean their feathers and skin.

Resting on perches.

In summary, the two systems do not place “greater” or “lesser” emphasis on well-being, but rather have different definitions of well-being. The first focuses on the absence of disease and productivity, while the second adds freedom of movement and the expression of natural behaviors as essential requirements.

Environmental impact: a comparison of management practices

Intensive farms invest in advanced systems for waste and manure management, centralizing and controlling the impact.

However, the environmental impact must be assessed across the entire production chain:

Intensive farming: the environmental impact is linked to the massive production of feed (often grown in monoculture and using pesticides), the energy consumption of the sheds, and the high number of animals confined in spaces considered small by critics. Manure management is centralized but highly concentrated.

Non-intensive farming: manure can be used as natural fertilizer, and feeding can include foraging in the local area, reducing dependence on external feed. The impact is more widespread and integrated into the surrounding land. However, not all farms are managed in the same way, and a non-intensive farmer may be less careful. In such cases, there is a risk of uncontrolled environmental impact, as well as the risk of animals becoming ill or being attacked by predators.

The logic of commercial selection

Multinationals such as Hy-Line, Lohmann, and Isa Brown have spent decades developing proprietary genetic lines that are closed and ultra-specialized. These lines are the result of billions of pieces of data collected and analyzed, and are optimized for a single goal: maximum efficiency and productivity in a controlled environment.

The selection parameters are extremely precise and include:

Number of eggs per hen (over 300 per year).

Uniformity of size, color, and shell strength.

Feed conversion rate (how much feed is needed to produce one kilogram of eggs).

Docility and resistance in high-density environments.

Native breeds do not meet these requirements. Although they are highly valued in terms of hardiness and adaptability, they produce far fewer eggs, are uneven in size and color, and are not suited to industrial production systems.

The role of native breeds in research

This does not mean that native breeds have no value for research. On the contrary, their genetic heritage is of great interest for:

The preservation of biodiversity because they represent a ‘genetic bank’ of unique traits that could be vital for future poultry farming (e.g., greater resistance to new diseases).

Academic studies by universities and research centers study them precisely to understand the differences in nutrition, resistance, and adaptation.

Multinational companies focus on ultra-specialized genetic lines for quantitative efficiency, while native breeds, with their unique characteristics, represent a valuable resource for scientific research and biodiversity conservation.

The aim of www.moreaboutchicken.com and www.nutriamocidibuonsenso.it is to provide objective information that allows people to take their own positions without unnecessary rigidity.

Here are some more points to consider, based on frequently asked questions we receive:

“Are farm eggs healthier?”

In terms of basic nutrition, the difference between eggs is minimal. The main proteins, fats, and vitamins are almost identical in an egg from an intensive farm and one from a small farm. Scientific data confirms this. The significant difference may concern micronutrients, such as Omega-3, which vary depending on the hen’s diet. A chicken that scratches around and eats grass or insects may have a slightly different lipid profile, but this is not a substantial difference that makes an egg ‘healthier’ in an absolute sense.

“Are farm eggs better?”

Taste is a very subjective judgment. Farm eggs may appear ‘better’ or ‘tastier’ for a very specific reason: the hen’s diet is more varied. If the hen has access to pastures, grass, and insects, its yolk may become darker and its flavor richer and more complex. It is a matter of personal preference, not objective quality. Those who are used to the uniform taste of industrial eggs may not prefer such a strong flavor.

“Are farm eggs safer?”

This is the most sensitive point, and the reality is that safety is often better guaranteed in intensive farms, not the opposite. Intensive farms are subject to much more frequent and stringent health checks. They have very strict biosecurity protocols to prevent the entry of pathogens (such as the filter zone we mentioned here https://moreaboutchicken.com/biosecurity-in-poultry-farming-what-is-the-filter-zone/ ) and constant monitoring of animal health. In contrast, on a non-professional farm, it is more difficult to guarantee the same level of hygiene, safety, and traceability. The fact that an animal lives outdoors does not mean that it is less exposed to contamination risks (from wild birds, animals, or other external agents).

Essentially, the choice between the two types of eggs (free-range or intensive farming) depends on the priorities of the consumer. If you are looking for a product with a richer flavor and management that is closer to the natural cycle of the hen, free-range is a good choice. If, on the other hand, you are looking for a product with a level of safety and uniformity guaranteed by strict and certified protocols, intensive farming offers just that. Both systems have their pros and cons, and it cannot be said that one is ‘better’ than the other in absolute terms.